STUDENT VOICES | THE 2024 CHYNN ETHICS PAPER PRIZE BEST ESSAY WINNER

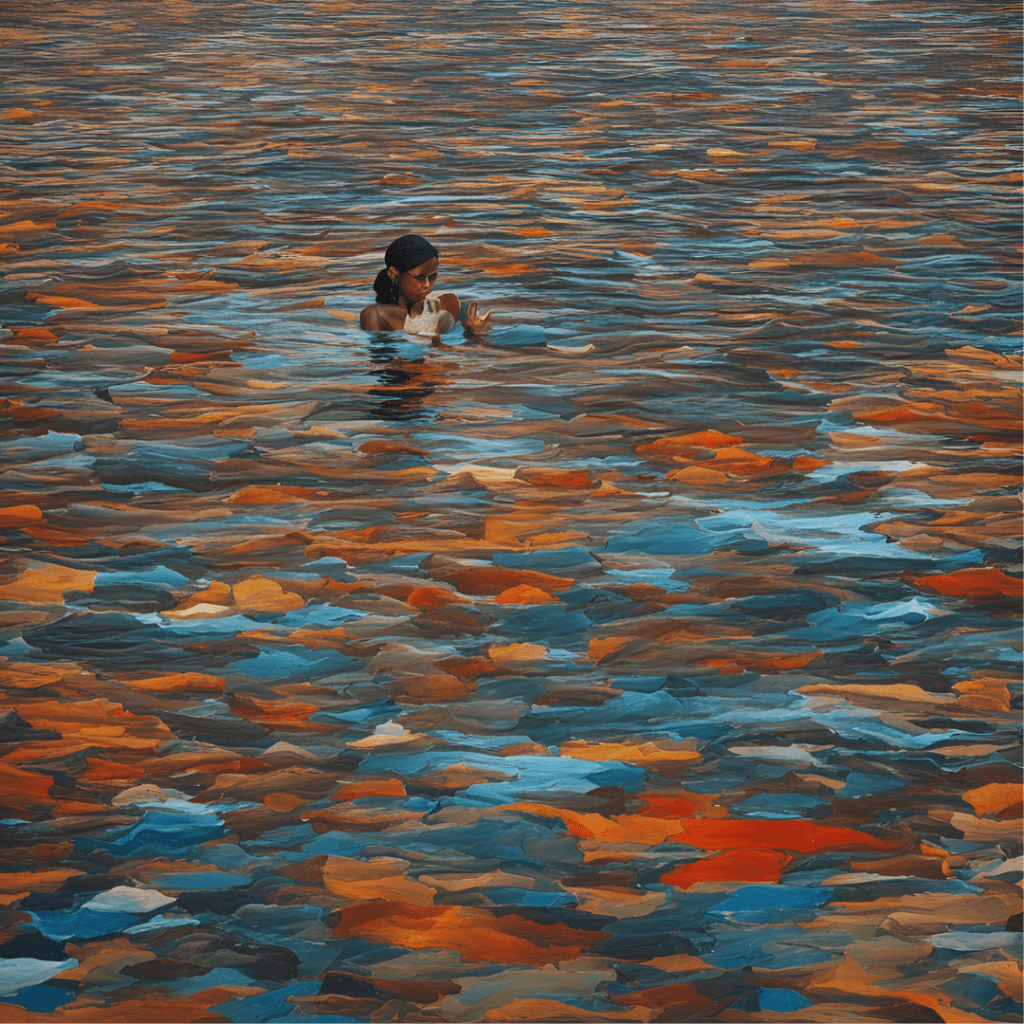

A Culture of Drowning: The Ethical Exigency of Investing in Public Pools

By Daniel Deeney, Fordham College Lincoln Center 2026

Last summer I worked as a lifeguard at a Philadelphia public pool. Philadelphia Parks & Recreation advertised bonuses for anyone who applied by a certain date, and I was desperate for a job. I called the offices of more than twenty rec centers, only one of which responded in a timely manner: East Poplar Playground. I later learned that the pool at East Poplar hadn’t opened since before the COVID-19 pandemic. Since I was the oldest and the only college student of those who had applied, the facility manager promoted me to head lifeguard and sole swim instructor before I received my preliminary certifications.

The pool’s opening was delayed by about a week, during which time I worked at a nearby rec center in the gentrified neighborhood of Northern Liberties. I thereafter started at East Poplar, located less than ten blocks away from the NoLibs pool yet remarkably less funded. A total of three lifeguards worked at East Poplar, the other two being high schoolers also in their first year on the job (the NoLibs head lifeguard had four years of experience on average). The Northern Liberties rec center had a surplus of kickboards to be used during lessons. East Poplar had none—I had to make do with dilapidated rescue tubes that, according to Red Cross guidelines, were unserviceable for use by lifeguards. The NoLibs staff issued signups for lessons and for the swim team, ensuring a consistent turnout, whereas different kids (and sometimes adults) showed up to my lessons every weekday. Sometimes language barriers precluded instruction; I was barely able to teach the Ukrainian refugees how to float because I do not speak Ukrainian and I had no translation service at my disposal.

I surmounted these difficulties to some extent, largely thanks to assistance from pool staff. The experience nonetheless showed me that significant disparities exist among the public swimming facilities of different communities in Philadelphia and, as further research evinces, the United States, primarily along socioeconomic and racial lines. The purpose of this paper is to assert the ethical exigency of investing in public pools in order to protect human life and promote equity.

Investing in public pools is a matter of public health in a country where drowning is a leading cause of death among young children and more than half the population cannot swim.1 When there are fewer public pools open, there are less opportunities for people to swim (and, critically, to learn how to swim). Even when public pools are open, it is difficult for people to learn what they need to know without proper resources, such as kickboards. At both local and national levels, lower-income and Black people suffer disproportionately from drowning injuries and deaths.2 In fact, the drowning rate for Black adolescents is more than three times the rate for their white peers.3 The United States’ culture of drowning could be easily reversed by investment in public pools. Such investment could take the form of wage increases for lifeguards to counteract the shortage, universal subsidized swim lessons, and the construction (and reconstruction) of more public pools. In Philadelphia, one of the major U.S. cities with the highest ratio of pools to residents, the ten pools that did not open in 2023 are located in low-income, majority-Black neighborhoods. Despite the presence of 61 pools in the city, “pool deserts” still exist in Philadelphia’s most underserved districts.4 In rural areas, replete with rivers and lakes but plighted by a dire paucity of public pools, drowning rates are 1.4 times as high as in cities and suburbs.5 More public pools with more resources are the solution to the public health crisis of drowning from which the United States so desperately needs saving.

Disinvestment in public pools also exacerbates another seemingly distinct public health crisis: gun violence. Public pools are one of the only means of recreation available to many children and young adults, especially during the summer months. They offer an escape from the tumult and violence that plague many underprivileged communities during a time of the year when young people, out of school and idle, are likely to seek diversions. The less dangerous those diversions are, the better for the health and safety of the community. According to a report from the Johns Hopkins Center for Gun Violence Solutions, under-resourced public services are among the chief conditions which increase the likelihood of gun violence.6 Of course, heightened investment in public pools would not be a panacea. Recent incidents at rec centers in violence-prone areas have indicated that pools are not bulletproof. That said, a person swimming or splashing or even lounging by the poolside is a person not engaged in violent behavior. In Philadelphia, 512 people were murdered and 1,800 wounded in 2022. 38 shootings occurred in the zip code of Dendy Recreation Center alone, where the pool did not open for three consecutive summers starting in 2020.7 Opening pools which have long been shuttered and building new pools in areas which need them could administer some immediate relief to the gun violence from which American cities suffer.

There are plenty of practical reasons which dictate the ethical imperative of supporting public pools. Besides mitigating incidents of drowning and gun violence, pools provide a way to exercise. The neighborhoods with fewer pools in Philadelphia have higher rates of diabetes, obesity, hypertension, asthma—health conditions ameliorated by swimming.8 They provide acutely necessary respite from the heat, magnified in cities by asphalt and crowded buildings and intensified by climate change. However, they also provide something many might not consider practical, but nonetheless essential: fun. There are rules in place to protect pool users—no running and jumping, for instance, and no dunking or diving. Generally, though, pool-goers, who are mostly youth, enjoy more freedom than in virtually any other space they inhabit. The pool is a space where friendships bloom, where creativity flourishes, where personal growth occurs at remarkable rates. The public pool serves to foster family and community ties; it is a shared space. Children experience some of their first successes and failures at the pool, where the stakes are low enough to render their failures opportunities to learn. The freedom which is afforded to people at the public pool engenders a sort of fun which can only be described as liberating. At one point this summer, while I was sitting on the deck and carefully surveilling the pool, the assistant site supervisor approached me with a cold Gatorade and, nodding towards the game of Marco Polo being played before us, said, “Man, can you remember the last time you were having as much fun as these kids?” And I honestly could not.

For more information about the prize, past winners, and submission requirements for 2025, please visit the Chynn Ethics Paper Prize webpage. The deadline to submit is TBD and is open to ALL undergraduates.

Works Cited

Bolin, Alice. “True Crime’s Ethical Dilemma.” Vulture, 1 August 2018, “Why Drowning Is a ‘Cultural Condition,’” KUOW, published August 5, 2014,

https://archive.kuow.org/news/2014-08-05/why-drowning-is-a-cultural-condition.

- Stacey M. Willcox-Pidgeon, Richard Charles Franklin, Peter A. Leggat, et al.,

“Identifying a gap in drowning prevention: high-risk populations,” Injury Prevention 26, no. 3 (2020): 279-88, https://injuryprevention.bmj.com/content/26/3/279.

- Mara Gay, “When It Comes to Swimming, ‘Why Have Americans Been Left on Their

Own?’” New York Times, July 27, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/07/27/opinion/drowning-public-pools-america.html.

- Daniel R. Taylor, “No closed pools: Why this Philly doctor wants every city pool open

this year | Expert Opinion,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 27, 2022, https://www.inquirer.com/opinion/commentary/philadelphia-swimming-pools-health-benefits-20220427.html.

- Gay.

- “Community Gun Violence,” The Educational Fund to Stop Gun Violence, last updated

February 2021, https://efsgv.org/learn/type-of-gun-violence/community-gun-violence/.

- Helen Urbiñas, “You say you love our city pools, Philadelphia. Then step up to be a

lifeguard. | Helen Urbiñas,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 15, 2022, https://www.inquirer.com/opinion/swimming-pools-philadelphia-lifeguard-shortage-parks-rec-helen-ubinas-20220415.html.

- Elise Young, “In Philadelphia, City Pools Bring Relief as Closed Ones Stir Frustration,”

New York Times, July 23, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/07/23/us/philadelphia-pools-closed.html.